Stargazer: Victoria Smalls

Have you ever felt like an outsider, even among people who seem similar to you? Victoria Smalls grew up on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, in the Gullah Geechee culture. Gullah people are descendants of Central and West Africans who were enslaved in the southern U.S. Their language combines African languages and English. When Victoria visited the nearest city just seven miles away, she was “devastated” when people laughed at her speech.

Victoria stayed strong. She became equally fluent in formal English and Gullah and earned a master’s degree in education. While teaching, she began to express her Gullah heritage through paintings. In 2012, she went to work at Penn Center, an organization focused on Gullah culture.

She now combines her passions in her work for the Zinn Education Project, visiting South Carolina schools to share African American history. Victoria lives on St. Helena Island with her daughter, Layla.

Q: What’s your favorite childhood memory?

People coming to visit . . . our farm. It’s 20 acres, and we farmed most of it, but it was a great place for Bahá’ís who were traveling to come and stay or camp . . . We could hear prayers being chanted in Farsi. We heard prayers in French . . . We hadn’t heard that before . . . We were hearing all these different languages in our house, and it was just so unbelievable . . . My fondest, my best memory growing up is being surrounded . . . by Bahá’ís from everywhere.

Q: Your parents had the first interracial marriage on St. Helena Island. Did they face racism?

In the Bahá’í Faith, you have to have permission [from your parents] to get married, regardless of your age. [This was] my mother and father’s second marriage [their spouses had died]. My father’s mother was living at that time, my granny. And he got permission to marry. And my mother’s hard task . . . was to get permission from her parents, who lived in Michigan . . . They refused to give permission for two years. And during that two years, she decided to move to back to Michigan so that she could convince her parents that this was what she wanted to do and this was right . . . And they finally . . . granted her permission after two years of her asking. Some of her siblings disowned her . . . And not until much later in life when they were maybe in their late 50s or 60s did they come around . . . a few of them, to apologize and to make amends for what had happened between them.

And they couldn’t get married in South Carolina. It was against the law . . . They had to get married in Michigan . . . and then came back home as a married couple with . . . her [four] white children from her first marriage . . . my father’s six children from his marriage, all black . . . and then [they later had] the biracial set of four. Fourteen children all together working on the farm, and it was a wonderful experience. It was the happiest time of my life living on the farm . . .

As a family, we were pretty protected on St. Helena Island. However, I would notice that my father would always prepare my mother for long trips or anything outside of 30 miles . . . He would prepare her to change a tire, to . . . look under the hood, because when . . . she would have a car issue traveling by herself with her children, her white children, her black children, and her biracial children, many people would not stop to help her . . . She would have to do it on her own . . .

Mostly, our struggles with racism would come when we would have to travel farther inland in South Carolina and throughout the states. But the thing is, we were always traveling to a Bahá’í event, so on the other side of that trip, at the end of that rainbow was this amazing, wonderful gathering of all these people . . .

On their farm on St. Helena Island, Victoria (age 13) helped her family raise most of their own food.

Q: What was your most challenging experience when you were a kid, and how did you handle it?

I was a teenager, about 14 [or] 15 years old . . . and on St. Helena Island, at that time period growing up, it was about 95–98% African American Gullah people . . . We were really protected on the island, and even though my father is black and my mother is white . . . because of their character . . . people really grew to love and respect my mother and father a great deal . . . We never really faced any racism at all on the island. Now across . . . two bridges . . . seven miles [is] Beaufort, which is considered the mainland. We would go shopping there for . . . necessities, maybe go twice a month . . . I remember going into Beaufort [to buy shoes] . . . and I opened my mouth and I spoke in my Gullah language, in my Gullah accent, and someone laughed at me, and I didn’t know what they were laughing at. And then I soon realized, oh, they are laughing at the way that I talk, and it hurt me so much . . . Being an African American . . . person on St. Helena Island is different from the experience just seven miles on the mainland . . . And it hurt to the point where I would stop talking. And then I started to suppress my language, try to hide it. And the little Gullah girl wanted to come out so badly that I would stutter . . . I would stumble over key words in the Gullah language.

Q: How does the Bahá’í Faith influence you in your work?

There’s not a time that I don’t talk about the Faith when I’m doing a presentation . . . I’m always mentioning the Bahá’í Faith. When I’m talking about history, when I’m talking about . . . anything regarding the Gullah culture, anything regarding Penn Center’s history . . . I’m always bringing in the Faith somehow . . . It’s just who I am in my life. That’s all I’ve ever known . . . Penn Center [was] . . . one of two sites in the South where whites and blacks could come together during segregation. This attracted all of these organizations, the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference], the Bahá’í Faith, Peace Corps, a whole bunch of organizations came to Penn Center during the segregated past because it was protected. It was a place where you could work out America’s challenging issues in a safe place and in the South . . . When I talk about the history, I talk about Bahá’í winter schools and summer schools [including the one] where my mother first came and brought her children . . . I am who I am because of Penn Center . . . That’s where my parents met after both of their spouses passed. They met there, and I’m in existence because of it . . .

Q: What is one of your favorite experiences in your career so far?

Being appointed a federal commissioner for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor . . . I’m able to go out and speak on a larger platform and to share the culture with people that have no clue about it, so when I became a commissioner, it made me feel like . . . I’ve been given a stamp of approval to be able to be more vocal about . . . this culture, the beauty of it, the uniqueness of it, how it is still living today and how to be able to preserve it . . .

In her former job as Director of History, Art and Culture at Penn Center, Victoria examined art depicting Penn officials meeting with educator Booker T. Washington and others around the early 1900s.

Q: What is something you find interesting about Gullah Geechee culture?

Gullah Geechee people are the people that have most of their Africanisms still intact. They have much of their African culture . . . being passed on from generation to generation. We have most of it intact. The people that were isolated in certain areas along the Gullah corridor . . . from the Wilmington, North Carolina, area down [to] St. Augustine, Florida, [and] from the Atlantic coast to 30 miles inland, is where most of the Gullah Geechee people were held captive, had to work, and were enslaved there. And certain areas were able to keep . . . a good portion of the culture intact . . . I’m saying that because . . . every generation that you’re in America, you lose a little bit of your culture, whether you’re German, French, Spanish, you lose a little bit of your culture, because you become a little bit more Americanized, and [there’s] nothing wrong with that. But then your elders have the responsibility of helping to keep some of your cultural tendencies within the family . . . So, I feel like I’m one of those culture keepers to help keep the culture alive because there are people that are still living the Gullah ways . . . There just aren’t that many people that know about it—the Gullah culture—at all. And then also I would love to see the Gullah language . . . [taught] in schools, just like you can learn Mandarin or French or Spanish. I would love to be able to see that in schools, and I understand there is a professor at Harvard teaching it . . . right now.

Q: Why are you passionate about this culture?

When I was working at Penn Center, I realized so many people that were coming from all over the nation and from different countries [had] never heard of the Gullah Geechee culture. And not just white . . . people; African Americans did not know about this culture. People in general did not know . . . that it existed. And there’s so much beauty in it . . . The people are beautiful. They are welcoming. They are loving. They are giving . . . I like to educate people about things . . . that have not been told, that have not been given a platform, but are so important . . . to the total story of America . . . It’s another story, another chapter [in] our story of humanity.

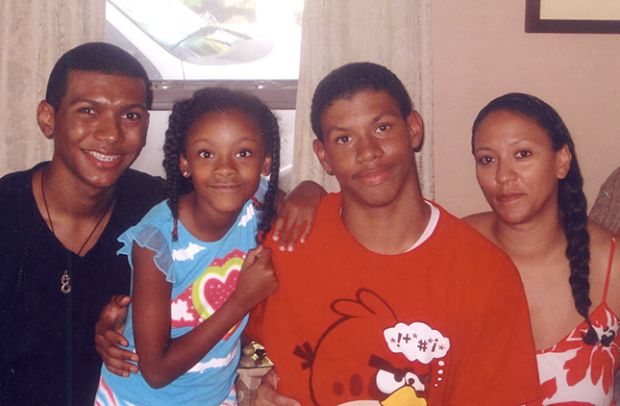

Victoria encourages her kids to appreciate their culture. Left to right are Christopher, Layla, Julian, and Victoria in South Carolina in 2014.

Q: What inspired you to become an artist?

I was going to a Naw‑Rúz party, and . . . we were going to play a gift exchange game that is supposed to teach you detachment . . . [The gift] was supposed to be something homemade, and I thought about baking something, but I wanted it to be something that someone could have for long term and not just for the moment of enjoyment . . . I was trying to think of something just unique, and I [had been] given the gift of these nine-pointed star cookie cutters . . . I traced them on a piece of paper. I had some pastels and I had some construction paper, and I made what I thought was a beautiful nine-pointed star piece of artwork, and I had matted [and framed] it . . . I was like, if nobody wants this I’m bringing it back home and I’m hanging it up my house—and it never came back home . . . It became “the prize to get” in this gift exchange game. And I felt so honored that so many people liked it . . .

Not too long after that . . . I would have, you know, the beautiful art calendars that you get with different artists and their artwork. Well, I bought this Jonathan Green calendar, he’s a Gullah lifestyle artist, and . . . once that [year] was over . . . I tore the pages apart and I framed them and matted them for my house . . . They were lovely and beautiful and depict the Gullah culture, so I wanted to surround myself with that . . . Then quickly I realized . . . I want my children to experience original art, and I didn’t think that I could afford original art from an art gallery . . . So, I decided that I’m going to create original artwork for my home . . . And my family and friends would visit my home and they would compliment me on it . . . And so, some of it I would give away and some of it I would sell . . . One day I decided I had so much artwork that I couldn’t hang it up on the walls of my house anymore, and I contacted . . . the Red Piano Too Art Gallery, and I told them that . . . I had some artwork, that I was from St. Helena Island, and I wanted them to look and . . . see if they were interested in selling it . . . I took in about 50 pieces of art. And the young lady who was receiving it would look at it, make a noise like hmm, and move it over to the side . . . without telling me what that meant. And I started to doubt myself again. And I was like, oh, goodness, she doesn’t like any of these. And before she got to the last one, I said, “Oh, well, I’ll start packing them away in the car.” And she’s like, “No you won’t . . . We’re going to take all of them.”

Q: What advice would you have for kids who want to be artists?

Create something every day. It doesn’t matter if it’s a stick figure, if you’re cutting out images [from] a magazine and making a collage, writing something down like your words, listening to music to help inspire you, create something every day . . . Make time for that . . . Do something every day to help spark that, and don’t keep it to yourself. Share it with someone. Share it with your parents, share it with your friends, so that they can see and know that you’re interested, and possibly even help you [and] provide some of the tools to continue sharing.

Q: What are your goals for the future?

Personally, I want to create more art. I want to be able to visually share my culture through my artwork. I’m also writing two books. I want to be able to share about how I grew up in the Gullah community and also share about other people who create within the Gullah Geechee culture . . . Professionally . . . I want to own my own Gullah consulting business . . . Also, back to personally, just know myself more spiritually, because I’ve always been a Bahá’í, but . . . recently I’ve been learning more about all faiths . . . I want to be able to learn more about faiths in general and religions in general, so that we can share our commonalities.

Q: This issue of Brilliant Star is about life skills. What three skills are important for kids to develop?

Well, compassion, number one. [And] believing in yourself . . . And sharing . . . Whenever we would grow crops in the field, [or] . . . we would go fishing . . . [we would share with] the elders in the community that could no longer fish or farm . . . My father . . . would go from house to house, either leave a bag on the porch or knock on the door and check on the elders of the community and take them food . . . I had that happen to me [in 2014] when my 16-year-old [son] Julian passed away [after an illness]. A young person in the community . . . left a bag of squash and zucchini and vegetables on my doorstep, and . . . it reminded me of what my father did.

Q: If you had one wish for Brilliant Star’s readers, what would it be?

It all goes back to compassion . . . I wish that all of them [will] become . . . compassionate beings.